King's Field IV (2001)

From Software

A cursed idol has laid ruin to one kingdom with plague and decay. Their expedition to return the idol to its origin, the now fallen and decayed Sacred City of the Forest Folk, has vanished without trace. Now with a knock on the door in the middle of the night, a hooded stranger has placed the idol in your hands. What torrid fate became the expedition for it to have now been returned to you? Nonetheless, the path is clear: the idol must be returned.

Seek the dark at the root of the world. Descend into the mist and the rot... it is the only option that remains for you.

The problem with King's Field is that it isn't honest about what it wants to be.

Let’s start at the top. The surface of the world, this cursed region you have ventured to, is near barren. Brown earth tones as far as the eye can see, broken up only by the occasional wound in the soil spewing rivers of lava. The few characters in this desolate space have all but lost hope. They eke out a meagre existence in the nearby mine (this is, naturally, full of poison). A strength the game carries forward for some of its run time is contrast. The land is not wholly bleak. A few specks of plant life dot the landscape, quickly scooped into your inventory for their life restoring properties. The jagged teeth of stony walls hint at a larger settlement, and indeed a community, that was once here. It’s one thing to build a fractured and calamitous landscape, it’s another greater skill to convey that weight of a space that used to be green and good, now turned to ash and mud.

Another similar moment occurs later in the game. Having penetrated through the surface areas into the sacred city itself, the game structures most of its world around the city’s central spire. You’ll weave in and around this spire, gradually uncovering faster paths back to earlier areas and descending towards the darkness and water at its root. Occasional excursions out of the city are made, at one point to the kingdom of the earth folk, but always you’ll circle back to this central point.

After many hours spent underground, you’ll unexpectedly begin to ascend again. Up and up a flight of stairs through the pressing dark until at last you find yourself on the surface and, beyond all probability, surrounded by the green and brown of leaves and bark. This is the former home of the forest folk, whose city you’ve been picking through the past several hours. Once they lived here, sheltered from the sun in the shadow created by the forest canopy. Later they tunnelled underground, creating the sacred city in the dark and the quiet. Later still they uncovered the rot at the bottom of the world. Not long after that, the dark destroyed them and their civilisation, scattering any survivors. The game creates a stunning contrast between the beauty of the gone away world in this pocket of forest, and the filth covered ruins you’ve been picking your way through. You’ll return to this place many times through your journey as it has a rare spring that refills your mana, but it will only ever be a temporary place of solace.

It’s this dichotomy between light and dark that the game seems poised to explore at a few key moments. Initially it seems easy to read as a conflict between the goodness of the surface world, of the life gifted by the light that created an entire forest capable of supporting a civilisation, and the rotten stagnancy of the dark. A simple fantasy story about a champion of the light vanquishing the dark.

When you reach the bottom of the central spire, you may stumble into one of the game’s optional areas: the sunken city. At the bottom of the already gargantuan space of the sacred city lies another even older, even more thoroughly destroyed civilisation. Most of this second city you never visit, long since swallowed by water as it is, but the few glimpses you get are tantalising. Unlike most of the game, there is no score, no ambient music, nothing but the echo of your feet on damp stone and the gentle sloshing of water among the bones.

A trick the game loves to pull is showing you areas that you’ll later reach. Sometimes this is done in small ways, building up a single area or indicating the presence of a secret movable wall. Other times it’s done over a much larger area, revealing areas below you that you won’t reach for hours to come. Almost always if you can see a place, you will go there at some point. It really lends to the presentation of the spaces you explore as a single contiguous space, unbounded by levels, loading screens or cutscenes. This was a place where people lived and eventually died. The sunken city is the exception to this spacial rule. You can see parts of this city stretching down through the water which you will never reach. They stretch down and down and down into the cold and the wet and the dark, always unreachable and unknowable.

It’s here that we learn just a few fragments about the people who lived here. They worshipped the dark, valuing the peace and calm it brought. Eventually it grew in power, taking on a will of its own. It destroyed their civilisation and they sealed it away down here in the calm dark waters.

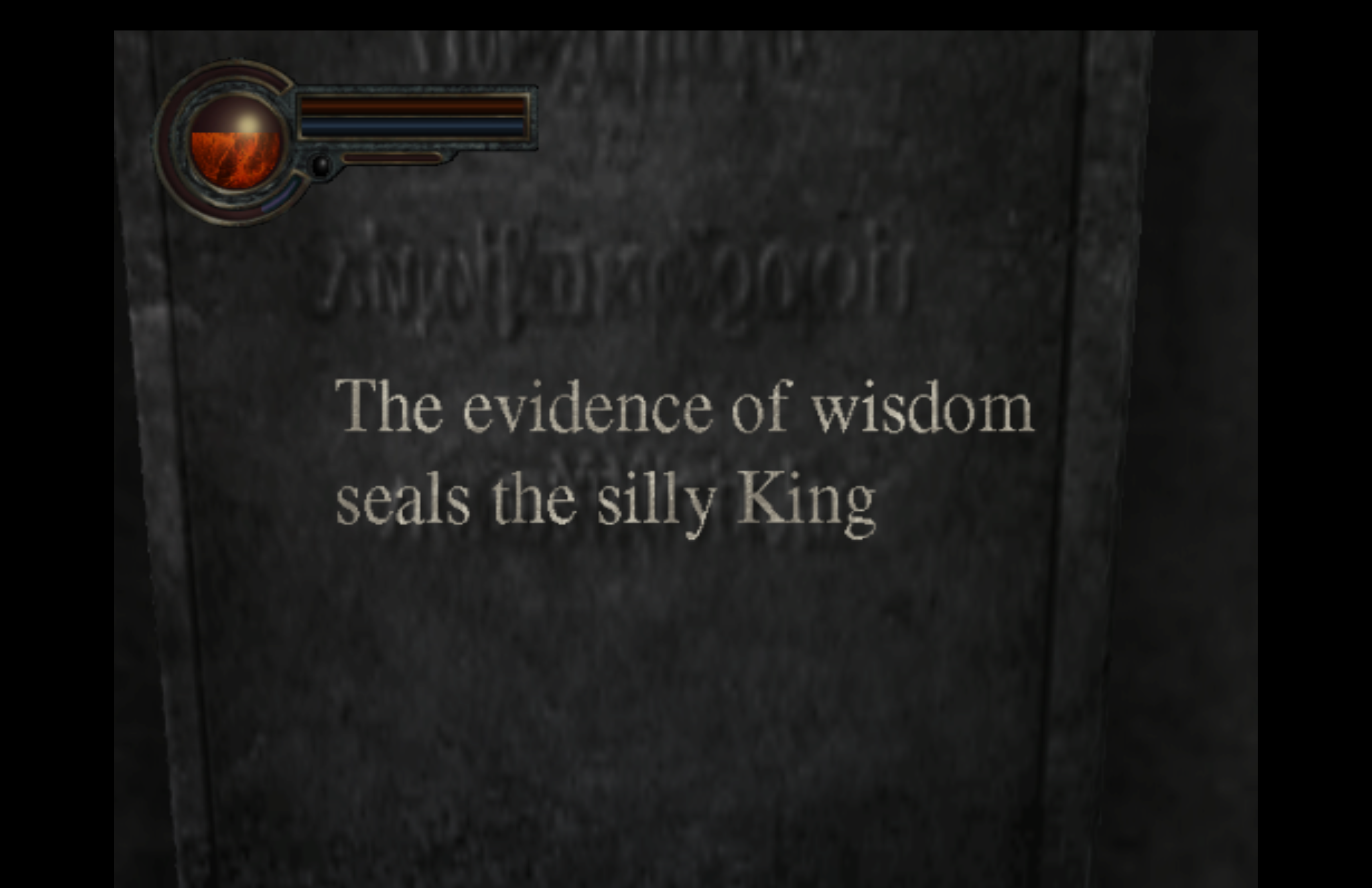

Importantly we can see a contrast with a similar crisis the forest folk once faced. Rather than the dark, they were almost consumed by the light. A shrine was built to both harness and worship the light, but as with the dark civilisation, unbalanced worship seems to have led it to gain its own power, turning into an object of fear. In that fear they were forced to seal away their then monarch, consumed as he was with blinding reverence to the light.

What becomes clear is that both forces represent more than simple concepts of good and evil and that either is dangerous if unconstrained. The dark, broadly representing stillness and calm, can lead to stagnation if unchecked. Several key milestones of the game involve reaching or restoring the flow of magical fountains capable of infinite health and mana restoration. In contrast the still waters found at the base of the central tower and the lost civilisation are worthless to the player. In their stillness they’ve become stagnant.

There’s also some sense of the need for a mediator between these forces. Here we can think of the forest that once protected the forest folk. It cast shadows on the earth for them to live in, sheltered from its intensity in the shade, but not wholly apart from the light. As a stone dedication we find so neatly puts it: "Our Mother of Nature, cover us with your canopy of greenery, guard us from the blazing sun that melts our bodies."

When, many hours later, the player finds the dead leader of the expedition, he clutches close to him the Ultimate Sword. Even later in the game, we can defeat the light addled king and push through to the forest shrine. There we can infuse the sword with light and it into the Divine Sword. “The legendary Sword. It deflects light and wards off the dark”, reads its description. There we also find the bones of the final king of the earthfolk, fallen to despair when his son, entranced by the darkness, broke its seal and cause the city’s doom. “When the light becomes stronger, the dark does as well”, his spirit tells you as you ponder his bones.

In a similar way the Divine Sword and more broadly the player are cast as a mediator between the light and dark. You harness the magical powers of both over the course of your adventure while being overtaken by neither. Where one old king was consumed by light, and a fallen prince by darkness, you stand firm against both forces.

Unfortunately the game is structurally extremely biased towards interacting with the dark and the problems it is currently causing in the world. For all the space I could give the ways in which the game sets up and explores the contrast between light and dark, the unfortunate reality is that by volume and experience, this takes up very little of the game. Experientially, the game is instead about dealing with the agents of the dark, the creatures and the hazards that lurk within it. It’s they who destroyed the sacred city. It’s they who presumably sent the cursed idol to the outside world. It is they who butchered the expedition attempting to return it, killing or hideously transforming them into more agents of the dark.

It is extremely hard to square off a few very small side areas with the hours and hours of demonstrable harm to the world and your own personal safety. For as strongly as the game is able and willing to contrast the the glimmers of beauty from a distant world with its current wreckage, it is virtually uninterested in portraying the dark as anything other than a conquering and malevolent force. A handful of bones in a few solitary side areas simply doesn’t cut it.

And then there’s the ending. At the bottom of the world you trudge through an ancient battlefield. This is where the forest folk battled the dark and lost. The bones of their fallen champions and shattered golems litter the area. You replace the idol to its pedestal and… it shatters to nothing and you are plunged even deeper into the dark.

Here you find what remains of your fellow dark-seeker. The former prince of the forest folk is now half melted into a throne of flesh and bone. If you haven’t empowered the Divine Sword you slay him and take his place. The dark will rest for now, but in time the idol will find its way into the hands of another would be dark seeker and this whole process will begin again.

Otherwise, in a slightly longer sequence the entire realm of Dark calcifies and shatters, sealed away forever by the power of the forest. Sunlight and hope flood the blighted lands and the wounds inflicted by the dark will slowly heal. You will return a hero, your ascent to both the throne and into legend assured.

This is frankly a ridiculous last minute swerve. Scant as these themes were, this ending abdicates any responsibility of actually seeing them through to the end. It posits a straightforward rote fantasy story in which the champion of the light defeats the dark when that is not the story it has been telling up to this point, either through its gameplay or its words.

Consider another game, Diablo. As another dungeon crawler, that game is structured in a similar way. You also start at the surface, gradually descending through dark underground labyrinths along the way. Upon reaching hell you slay the titular Diablo's mortal body, before taking the stone that contains his soul and driving it into your own forehead. This will contain Diablo, for a time at least, but whatever good you have done for the world, you will one day in turn undo. When Diablo finally breaks its chains and takes your body for the next go around the cycle, there will be nothing you can do but watch. It’s a delicious final twist, complimenting the dark gothic tone of the whole game, but also acts as a fitting capstone for what you had been doing the entire game. You killed monsters and demons alike, sifting through their remains for scraps of power you could add to your own. In the end though, this is what all that stolen power brought you: a little time and a slow demise.

In its play, KF4 often drives in similar directions. While there are exceptions, the majority of the enemies in the Sacred City do not respawn. Through your adventure you cleanse the place and sift through the dirt and bones that remain for the power to push further and further down. The king of the earth folk was a weak ruler and fell to the dark's influence, but you weren't. You killed him and took his strength as your own. The prince of the forest folk sought the dark, they stared it down and then they blinked. You find them melted into their throne of flesh and bone. Not you though, where the dark stares at you, you stare back.

This is a game about your bloody ascent to the throne, but in the end the game doesn't treat it like that. You strike down the dark avatar and all is well. Any complexity the game toyed with is abandoned by the wayside for a stock fantasy ending no more challenging than Disney's 'The Sword in the Stone'. And for a game that is so willing to challenge its players in so many different ways, and trust that at least some of them will find value in those challenges, I just do not understand this decision.

Consider From's own back catalogue. Three years earlier they released King's Field spin off 'Shadow Tower'. This was a much darker title, leaning more on horror imagery, but followed the same basic setup as all their games: a champion standing against the darkness. In the end though, you end up consumed by the darkness you sought to save others from. When you fell the dark king, you're offered a crown that grants any wish. The choice is instant, you are revealed as the conquering monarch you always were.

Some miscellaneous things:

- When the past king of the forest folk got a little too into worshipping the light, he was sealed away in a room just two rooms away from the city's throne room. He then spent the next ??? years haunting the corridor next to him threatening everybody who walked down it, chilling with half dozen ressurected skeletons in his locked room, as well as throwing lightning bolts at anyone on the surface over the top of his locked room. This is extremely funny to me that this was all going on both before and during the Sacred City's collapse.

- As quite a few people have noted over the years, this game has a surprising amount in common with Dark Souls 2. Some is this isn't unique to that game, all From's dark fantasy games draw to some extent from the whole of KF in various ways, but there are some more specific ways DS2 draws on KF4. Some are extremely overt, both games have a map in their central hub on which flames gradually ignite, tracking your progress through the game. Both have ominously sealed door's that inform you vaguely that you need the authority of the king to pass (each solved by wearing the 'King's Ring'. There's a spot in KF4 where you spot a skeleton ringing a bell ominously in the distance. The realisation swiftly hits that they've just summoned about 10 fellow skeleton archers to fill you with holes. Its good as a gag, but not really intended as something you influence, just something that happens to you and then you have to cut your way through. AFAIK its either very hard or impossible to kill the bell skelly. DS2 takes this and develops it into a whole area mechanic. Undead rise from the ground and start making their way towards ominously placed bells. If they manage to reach them, then powerful spectres are raised to attack you, requiring juggling killing the bell ringers and destroying the spectral creatures' graves to permanently remove the threat. I'm not sure there's anything hugely interesting to draw out from these parallels, but it does go a little way in explaining why DS2 is the way it is.

- I am hardly the first to point out the failings of From's current and historical depictions of women in their games, but I'm comfortable adding this game to the pile. We have:

- A sick mother and daughter passively waiting for their (dead) patriarch to return, a role which the player instead fills.

- A demure elf maiden, last guardian to the forest.

- A poisonous snake emporess (DS2 has big shades of this also).

- A purple skinned boob armoured succubus type enemy.