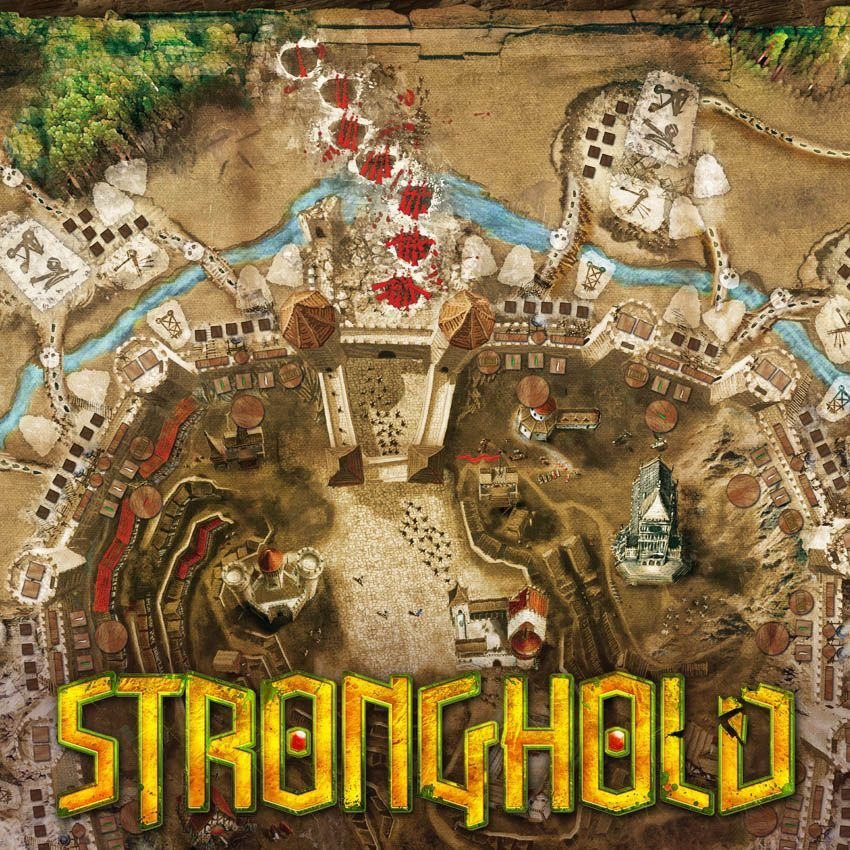

StrongHold 2nd Edition

Designer: Ignacy Trzewiczek

And also a semi related tangent on The Carpet People

Its a well worn set up. The seemingly infinite forces of darkness arrayed against the small force of beleaguered defenders is a familiar setting for anybody passingly familiar with The Lord of the Rings Terry Pratchett's Carpet People, but more on that later.

In Stronghold's case, one player is charged with managing the assault, while the other mounts their defence. If the outer defences are breached, at all, the attacker immediately wins, while the defender '''wins''' by surviving seven rounds, narratively framed as a day each. They win at this point not by virtue of a well timed relieving army emerging from the undergrowth and some approriately heroic charges but merely by having survived long enough both for their fleeing caravan of civilians to have reached the next fortress before the incoming horde runs them down on the road. The narrative presented is not one of triumph, but instead an attempt at turning a crushing defeat into some sort of victory.

Appropriately then, the most key resource of the game is time. Not merely the round marker, creeping day by day towards 'victory' for the defenders, but time as embedded in the key mechanisms of the game. On the attacker's part, they have difficult choices to make. Everything they might want to do to expedite the seige: moving troops, building seige weaponry etc, costs them time needed to fulfill that action. Sure its nice to have some trebuchets, an opponent not having walls left by the time the orcs get there is certainly a positive, but every time the attacker takes an action, they spend a little precious time and pass it on to the defender to spend on their defense plans.

So the attacker is essentially weighing every action, betting on whether or not their investment of time is more valuable than the time that would then offer the defender. Its an exciting thread then that binds the two players. Each pull towards the attacker being promptly tugged back by the defender, but how strongly each person is pulling on the thread not being evident till right at the end.

It follows that the defender relies almost entirely on the attacking player to dictate the pace of the game. They may spend their time on a variety of actions. Cauldrons, cannons, troop movement and training etc. As such, time is an immensely precious commodity with never enough to go around. The defender can never quite get ahead of the attacker. A cannon will pick off approaching units, but it will not and never can be enough. Defeat cannot be averted after all, only staved off.

The cumulative effect of this is an exhilirating kind of pressure. The kind that leaves you feverishly counting up attackers and defenders, trying to balance your longer and shorter term comittments. Sure, building a tower for your archers to better pick off approaching attackers will be a cumulative benefit in the turns to come, but maybe its better to shuffle a hero into the most hotly contested wall section right here and now to avoid taking casualties. Then again, if you spend precious time to move your hero, what if the attacker shifts their focus, then you'll have to spend even more time shuffling that hero back again. Its difficult to see through the sea of choices. You spend the time and hand you're dealt, no more no less.

The flip side of this though, and probably the biggest turn off for a lot of people is that the game is both moderately mathsy and can be lost not through a true strategic mistake, but simply through your brain running out of bandwith. Its happened multiple times that I'm so caught up in trying to balance the numbers, to dampen the flames in every section just enough to get to the next turn that after confidently telling myself I've covered every angle, the resolution phase then smacks me with the painful truth that one of the wall sections simply exited through the back door of my mind at some unknown point during the last turn. A mildly embarrasing game over.

Whether you consider this a positive, or the worst idea you've heard in your life then, is whether you view this potential loss as an illegitimate outcome, resulting less from a 'fair' struggle between each side's mechanisms and more from how long the defense is able to keep their focus over the potential ninety minute length of the game. Certainly it does fit the themes of the game, much of the strategy of the attacker relies on pushing and pulling on different threads around the board, trying to divide the strength of the defenders and force them to overcommit to different areas, before refocusing the attack on a weaker area. For me at least, being mentally pushed over the brink by these differing sources of pressure was a satisfying enough conclusion, but I wouldn't fight anyone who refused to play again after that.

A Semi Related Tangent

Terry Pratchett began work on The Carpet People in his late teens, and when it was published in his early 20s it was his first published work. Regrettably this version is long out of print and I'm not paying four-hundred quid for a write up about Stronghold. It was by all accounts however, a very close riff on Lord of the Rings, albeit transplanted onto the delightful setting of a carpet and the adventures its tiny peoples go on. Two decades later however, when Pratchett was already a decade deep into the now much more well known Discworld series, he revisited and rewrote The Carpet People, leaving a version that's in much wider circulation today. The changes reflect Pratchett's development both as a writer and a person, being far more comedic where the original played its tropes straight, and being broadly more critical of those tropes. As one example of the former, a late scene involves a riff on the corresponding section before the black gates in The Return of the King. Where in the original, the mouth of Sauron attempts to bully the Gondorians into surrender and they say no, in Pratchett's 1992 version, one of the characters takes the messenger's demand to 'throw away your weapons' literally and throws their sword, killing the messenger. The follow-up punch line being a few pages later when the final battle begins and he has to ask around for a spare sword. (Oddly the Jackson film adaption would also add this change a decade later, with Aragorn decapitating the mouth of Sauron instead, but leaves out the comedic tone.)

For the latter, we can look to the Wights, a straightforward elf insert, first people of the Carpet and soon to leave, and substantially different in the reimagining. In this new version they have the power to remember their entire lives from the moment of their birth. Paradoxically, however, this renders them powerless, bound to follow the 'thread' of their lives to the bitter end no matter how it arrives. Part of the climax of the book then, relies on the cracking of this deep held assumption:

The ring of defenders was pushed back, and back, until it was fighting in the ruins of the city itself. And ... was beaten. Valiantly beaten. They lost. Ware was never rebuilt. There was never a new Republic. The survivors fled to what remained of their homes, and that was the end of the history of civilization. For ever. Deep in the hairs, Culaina the thunorg moved without walking. She passed through future after future,and there they were, nearly all alike. Now she moved without running, faster and faster through all the future of Maybe. They streamed pasther. These were all the futures that never got written down-the futures where people lost, worldscrumbled, where the last wild chances were not quite enough. All of them had to happen, somewhere. But not here, she said. And then there was one, and only one. She was amazed. Normally futures came in bundles ofthousands, differing in tiny little ways. But this one was all by itself. It barely existed. It had no right toexist. It was the million-to-one chance that the defenders would win.

...

Amazing that they should have even one chance of a future. Culaina smiled. And went to see what it was ... What you look at, you change

Invigorated by their new found realisation that they might take control of their own destinies, the Wight join and turn the tide of the final battle. From this one small change of outlook, that step of imagining the world not as you expect it to be, but as it could be, flows everything: a new and more equitable society, democracy, rights for women, the end of empire.

And the wights foughtlike mad things ... worse, they fought like sane things, with the very best weapons they'd been able to make, cutting and cutting. Like surgeons, Pismire said later. Or people who had found out that the best kind of future is one you make yourself.

Where this relates to stronghold, though, is in its treatment of the Mouls. I suspect that Pratchett had some growing awareness in the 20 years since its conception of the highly racialised aspects of Tolkien's fantasy races, especially those deemed as evil by the narrative. While I don't think the changes are so substantial as to wholly escape their influence, the treatment of the Mouls is still an interesting departure. In one instance the book notes that basically every race, including the Mouls, has their name translate into some variation on 'the people'

Then one day the tribe meets some othe people, and gives them a name like The Other People or, if it's not been a good day, The Enemy. If only they'd think up a name like Some More True Human Beings, it'd save a lot of trouble later on

In the end, the captured Moul leader is amazed that the new leader chooses to spare him, a clear break from how the previous empire would operate and against the protests of a surviving noble character. These are ultimately not enormous changes and I think the revised version is still very much in Tolkien's orbit, but more importantly, Pratchett realised the problems with his original work in 1992. This is not a new criticism.

UH OH

All this is a long winded way of saying that Stronghold doesn't even make the attempt and in the process crashes its medieval cart straight into the castle wall.

The game leans heaviliy into its stock fantasy trappings, a generic and faceless horde of orcs, goblins and trolls descending upon the civilised world, concerned with nothing but destruction of their civilised enemies whom it should be noted, have a distinctly Christian sense to them. Much of the art evokes medieval European civilisation and while the attackers have access to various Magicks, 'bloodstones', 'possesion' and the like, in comparison the defenders have no recourse to these pagany feeling abilites. Instead they have the cathedral. Spend enough time in prayer there and an 'unearthly glare' will shine on a single wall section, preventing all combat there for a turn. The overtones are pretty clear. I would call it a clash of civilisations, but that would also imply too much about the orcs. They have no characters, no names, even in the 2 page introductory short story, and no motivations beyond foul destruction and tearing down what civilised people build.

I mentioned earlier how commonplace the desperate battle is in a certain type of pulpy fantasy; a potent narrative device in the right hands, a played out cliche in others. Regretably though, Stronghold perhaps owes a little less to Tolkien, and regretably more to 300 in this case. Oops.

300 is a comic written by a man who hates brown people. It was then turned into a film by a director about whom, at least personally, nobody seems ta have anything bad to say. We must assume then that he is merely a fool, a man whose body of work suggests that he puts absolutely no thought into the imagery of his films and what it conveys beyond trying to look cool on the shallowest possible level. 300 hates women, gay people, disabled people, any form of deviance from some nebulous sense of western culture and so on and so forth.

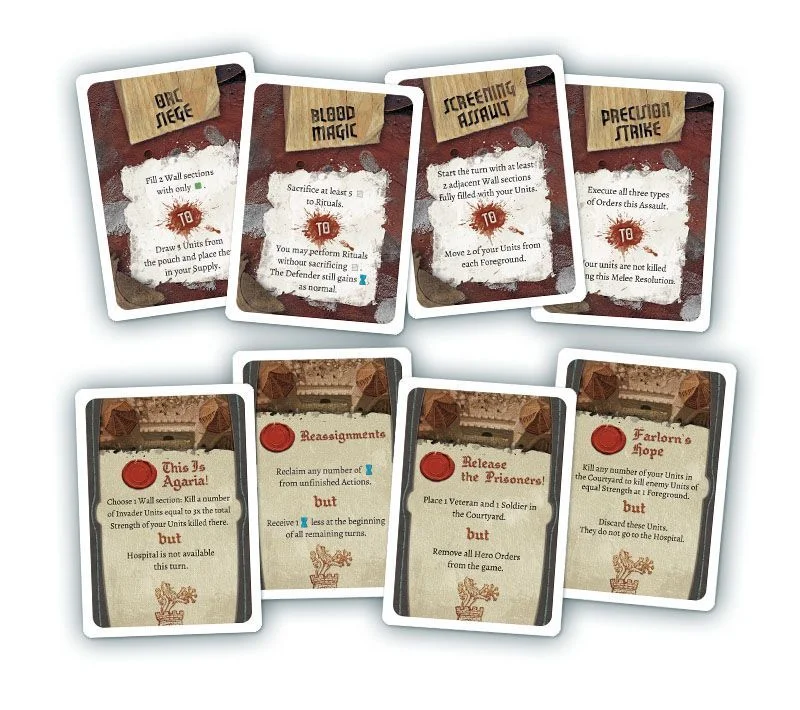

The defense has access to a few defense cards, essentially one time benefits for long term drawbacks. They're great, they perfectly represent the central dilemma of the game; sure tearing down the hospital rebuild your walls probably isn't great for your long term health, but when you're trying to get to the next day, sometimes you've got to do the desperation moves. They are less great when one of them is referencing the whole 'this is sparta' deal that was going around in the late 2000s and early 2010s for a good while. I don't want to overstate this, it is just one card, this even with all its other issues this game is a million miles from the imagery of 300. Yet all of this taken holistically makes me think that the people designing this game were completely on top of things as far as the emotions they wanted their mechanics to convey, then proceeded to put absolutely no thought to their theming beyond that save for a grab-bag of stock tropes and whatever seemed like a cool reference. I'd like to say that this doesn't matter that much; that it takes place mostly in the margins of the game, in the art and a few card descriptions; but that would be tacitly giving in to the argument that all this is just an excercise in mechanics, that we're all just sitting here pushing around brown cubes in Puerto Rico that have no greater meaning, and board games deserve better than that.